By Julia Katila, Postdoctoral Research Fellow at Tampere University

[bg_collapse view=”button-red” color=”#ffffff” icon=”arrow” expand_text=”What’s a Squib?” collapse_text=”Hide this explanation” ]

In the EM/CA community, we all know the importance of “putting our work out there”: discussing our findings and impressions with other researchers is not only a way to avoid (or at least reduce) the risks of an individualistic analysis, but also, and above all, a precious resource for progressing and improving our work. Long before the publication in a journal, in the midst of the analytic process, collective scrutiny and discussions are fundamental practices to provide the researcher with suggestions, comments, references and even beneficial doubts.

For this reason, this section of the ISCA Forum Newsletter is dedicated to “squibs”: concise articles containing preliminary, in-process analyses in an EM/CA perspective. In this section, researchers can present their work-in-progress findings to the ISCA community in order to generate discussions and collect observations, suggestions, useful references and potential publication venues.

CALL FOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Would you like to share your in-process analysis to have some feedback? Send us your squib! Please note that your contribution should satisfy the following requirements: 1) not exceed 2000 words (2200 for non-English data); 2) contain one or two transcripts and relative preliminary analyses; 3) illustrate a phenomenon fitting within the existing framework of EM/CA analyses.

Please email your contribution to pubs@conversationanalysis.org

[/bg_collapse]

Introduction

Human beings are prone to showing affection through touch. For instance, caregivers gently touching their offspring is perhaps the most primordial way, among the human species, to express and experience love and affection. Something similar takes place in adulthood between romantic partners: when close to one another, “lovers cannot help themselves from weaving their bodies together in various forms of intertwinement and embrace”, to use Maclaren’s (2014: 96) words.

However, if touch is indeed a primordial site for affection among human, why is it that romantic partners sometimes become more distant from one another and there is not as much physical touching that either one or both parties desire? Previous research has approached differences in willingness to touch through attachment avoidance, which refers to feeling discomfort with closeness and valuing independence (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2008). Even if it has been suggested that all people, despite their attachment style, benefit from touch (Debrot et al., 2021), attachment avoidance has been associated with more negative attitudes toward touch (Chopik et al., 2014).

While individual differences in affection style certainly play a role, in this study I will approach the accomplishment of affective touch among romantic couples from an interactional perspective. I use the term “trajectories of love” to refer to the embodied performances through which lovers seek touching and being touched in an affective manner. According to this perspective, the amount of physical touch in a romantic relationship is not just the result of individual features but, rather, also seen as an interactional phenomenon stemming from the relationship-specific interaction practices a couple has established within their history. Therefore, embodied relationships are something people (re)produce in their everyday interactions (Gan, 2020; Goodwin & Cekaite, 2018; Katila, 2018). Drawing from this interactional perspective, physical togetherness and the “license to touch” the partner are also viewed as a product of continuously practiced relationship rituals (Goffman, 1971), within which the history of previous interactions and the moment-by-moment unfolding of interactional negotiation over physical togetherness and separation intersect.

I utilize a video-analytic perspective to uncover the interactional accomplishment of affectionate touch among romantic couples. With a focus on intercorporeal — co-experienced and co-embodied (Merleau-Ponty, 1962) — aspects of embodied interaction between Finnish romantic partners, I employ interaction analysis (M.H. Goodwin & Cekaite, 2018) to describe the practices through which the participants physically or verbally request, comply with, or resist touching or being touched. In this way, I discuss how the participants negotiate their personal space and “appropriate” moments to touch in an embodied way.

The data

So far the dataset entails video- and interview data for seven romantic couples, whose everyday lives I videorecorded for 10–20 hours per day over seven days. In addition, I interviewed the couples (each participant first separately and then the couples together) by showing them videoclips from their own interaction. Thus far, the study includes a collection of at least 250 naturally occurring cases of kissing and hugging. A supportive statement on the part of the Ethical Committee was obtained prior to data collection, and written consent was requested from each participant. The participants could withdraw from the study at any point, though that never happened.

Especially given the intimacy of the setting, videorecording may have had an influence on the participants’ behavior. Indeed, sometimes the participants explicitly oriented to the camera or talked about being videorecorded. However, all the couples also mentioned that they often forgot the presence of the cameras. The participants were also instructed on the usage of the cameras, and they could turn them off at any point. Sometimes, this happened, for instance, when they were about to have sex.

A large share of the kisses and cuddles in the collection can be labelled as so-called boundary intertwinings – practices such as greetings and farewells, which mark a transition into increased or decreased access to one another, or other supportive interaction rituals, such as remedial or celebratory interchanges (Goffman, 1971: 79; Goodwin & Cekaite, 2018). However, sometimes, the moments of affective touch were initiated spontaneously, “outside of the established rituals”, simply due to the need and desire to be in touch. I have chosen one such spontaneously initiated trajectory of love for a detailed analysis. I will exemplify how touch and the following affective moment is initiated in the midst of daily activities.

The successful accomplishment of an Everyday Trajectory of Love

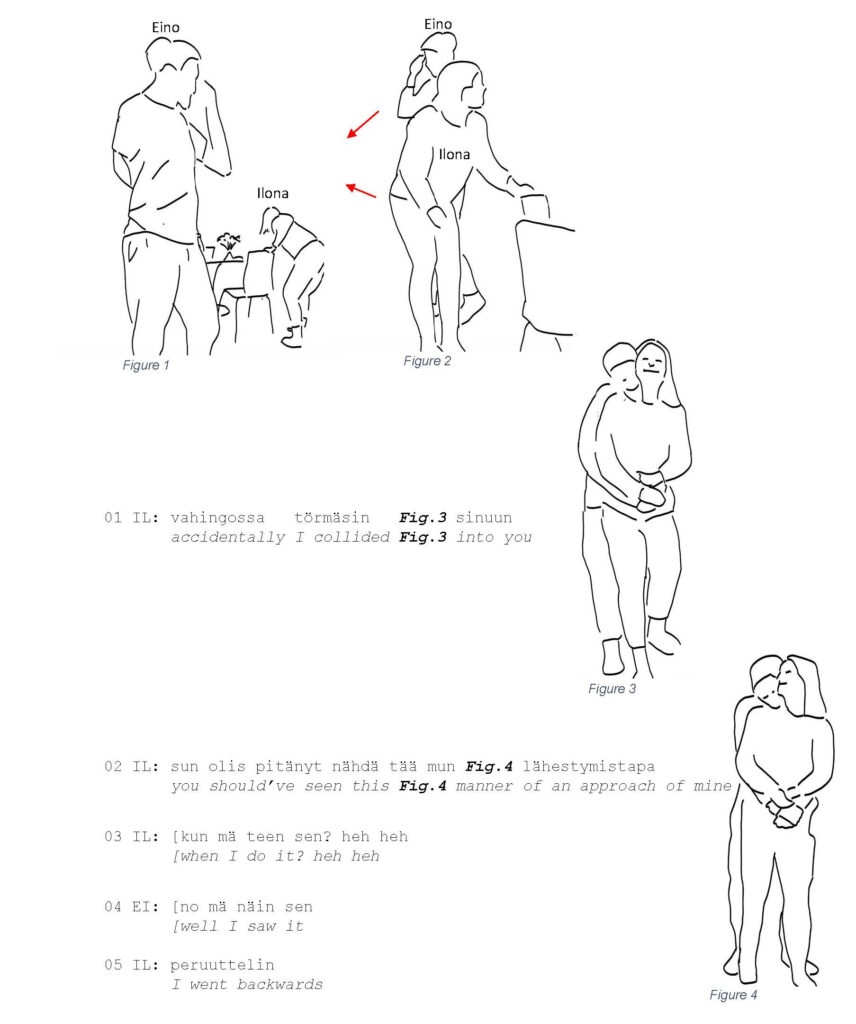

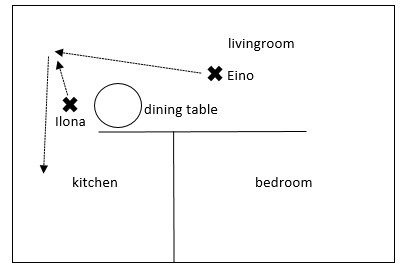

In the following analysis, I will unveil some of the ways in which the participants initiate “trajectories of love” in their everyday lives, enabled by their “daily round” (Goffman, 1959), intersecting activity trajectories and affordances of their bodies and the environment. I will consider a heterosexual couple who had been together for 4–5 years by the time of the recording. The episode occurs just after the participants have finished their day’s work. The male participant, “Eino” (EI), is about to do some minor renovation in the house, and for this, he needs to pick up a measurement tape from the kitchen. As he is walking toward the kitchen from the living room (Image 1, the floorplan), the female participant, “Ilona” (IL), who is standing by the kitchen table, is picking up something she dropped on the floor.

As Ilona is bending down, with her backside facing the passageway to the kitchen, Eino and Ilona’s movement trajectories intersect. Afforded by her current posture (bending down) and the incidentally intersecting pathways of the participants (Figure 1), Ilona starts to reverse towards Eino (Figure 2).

The trajectory of love is initiated by momentarily halting and departing from the ongoing movement trajectory in order to approach the other person. Holding her body bent-down and backside in front, Ilona approaches Eino (Figure 2). Immediately, when the bodies reach one another, Eino encloses Ilona in a hug (Figure 3), and the two merge into “tactile intercorporeality” (Katila, 2018). With their eyes closed to indicate a focus on feeling one another, Ilona simultaneously produces a playful account of her approaching movement – accidentally I collided into you (line 01) – uttered in a gentle tone of the voice. With Eino’s face against Ilona’s neck, the two form a mobile gestalt and begin to walk together toward the kitchen, still in the tactile arrangement (Figure 4). Framed in a gently humorous tone, in lines 02–03 and 05, Ilona further describes her unexpected movement trajectory and explicates that it was not really an accident. Eino provides an aligning response to this and a confirmation that he did see Ilona approaching him (Line 04). Something very important here, is the manner in which the other person’s approach is self-evidently accepted and aligned with. There is no moment of embodied hesitation. Rather, Eino immediately takes Ilona into his arms as she starts to move toward him. Approaching her partner backwards and with an intimate body part (bottom), Ilona’s action shows a great amount of trust that Eino will accept her embodied initiative. The timing of her body movement is precise too: she begins reversing toward Eino a good deal before he passes by so that the movement does not just surprise him but, rather, leaves him a second or two to react. As the two walk toward the kitchen, Ilona begins singing a well-known Finnish children’s song “Elefanttimarssi” (The Elephant March, composer unknown.). The song, perhaps inspired by the body posture and movement of the participants (moving together towards the kitchen), describes two little elephants who are “marching on, forward on a sunny road”. Initiating this playful and gentle interaction frame, the song sets a rhythm for the forthcoming kissing trajectory:

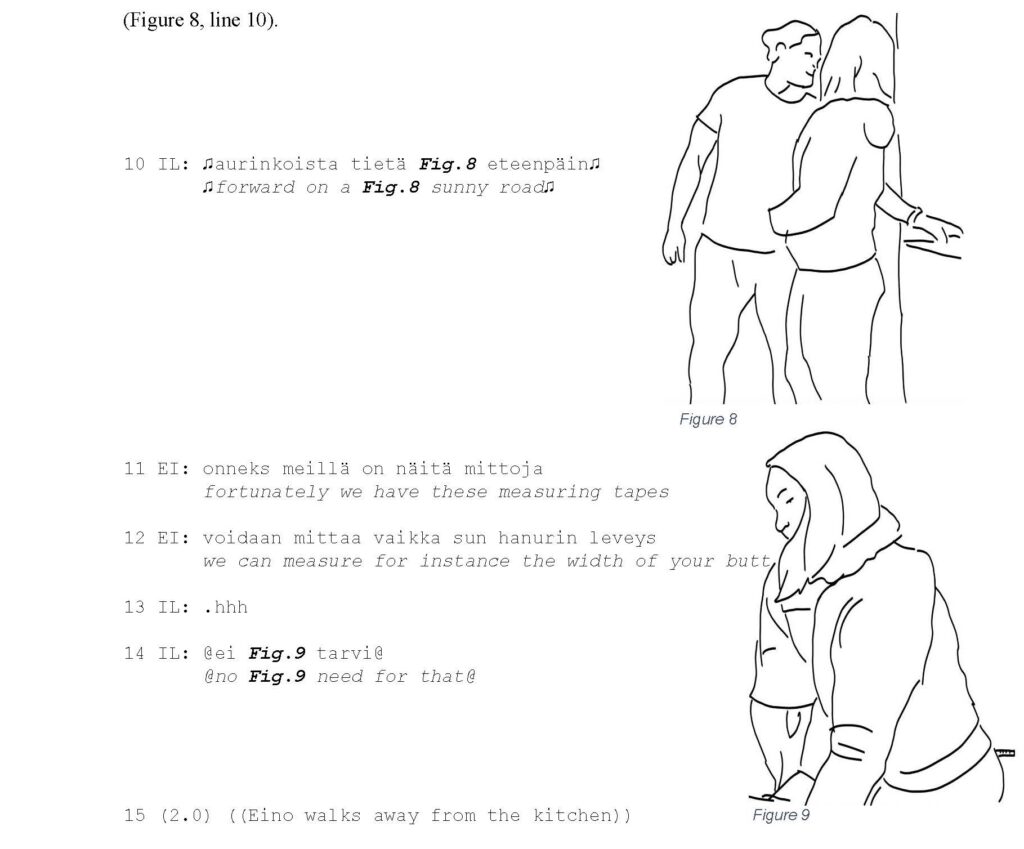

Ilona’s singing organizes a rhythm for the gentle kisses. Co-occurring with the first melodies, ♫two (.) little♫ (line 06), Eino gently pushes Ilona toward the doorframe and kisses her neck (Figure 5). Ilona then turns her gaze slightly towards Eino (Figure 6) and initiates a self-repair, oops I started with a wrong note (line 07). The break from the song coincides with a break from kissing, and Ilona turns her head slightly towards Eino and smiles as if apologizing for her “mistake ”. Ilona then continues the song with a “correct” note, ♫two little elephants were marching on♫, and turns around towards Eino in the rhythm of the song. Exactly as the first unit of the song is finished, Ilona and Eino face one another, and Eino approaches Ilona for a kiss on the lips (Figure 7). Eino then reaches for a measuring tape he was originally picking up from the kitchen as Ilona continues singing the song

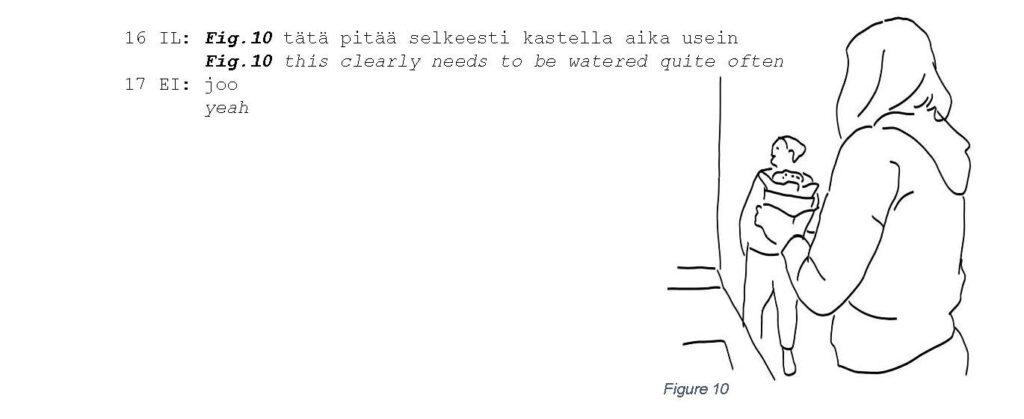

After the kiss on lips, a withdrawal from the love trajectory back into everyday activities occurs smoothly and step-by-step. During the moment Eino is reaching for the measuring tape and Ilona still continues the song (Figure 8, line 10), the two participants momentarily embody slightly misaligned trajectories: while one trajectory –singing the song – still contributes to continuing the affectionate moment, the other – grasping the measuring tape– initiates a return to whatever they were doing before the affectionate moment. However, Eino then creatively adopts an object belonging to his current trajectory, the measuring tape, as a resource to return to showing attention to his partner: fortunately, we have these measuring tapes we can measure, for instance, the width of your butt (lines 11–12). This expression, designedly humorous and perhaps including a sexual tone, is received by Ilona with a light smile and laughter (line 13). Eino is then upgrading his joke by lightly slapping Ilona’s behind with the measure (Figure 9.) This tactile gesture coincides with Ilona’s verbal response to Eino’s suggestion (@no need for that@, line 9.) Said in a smiley tone of voice, Ilona’s utterance still recognizes the humorous frame embedded in Eino’s action, but it shows that she has already withdrawn from the affection frame and started another activity. She has turned toward the kitchen sink to water a flower. Orienting himself to Ilona’s embodied cues, Eino also begins to walk away from the kitchen to continue his renovation (line 15). Ilona then picks up the flowerpot and initiates a discussion topic unrelated to the affectionate moment – watering the flower (line 16, Figure 10). The two continue their everyday businesses. Like merging into the trajectory of love, withdrawing from the trajectory of love thus occurs through subtle embodied negotiation over the next activity sequence, as well as through carefully attuning oneself to the other’s interaction projects and ongoing activities.

Conclusion

In romantic relationships, the participants are often seen as “entitled to” touch one another at any moment due to the nature of the relationship. My study initially suggests, however, that moments of touch and affection are carefully initiated, incorporating the resources of the local environment, and designed to fit the ongoing trajectories of daily activities. Here I have only provided a single case analysis of one trajectory of love, and more systematic analysis of more instances is needed to identify what attempts that are successful and reciprocated or unsuccessful and not reciprocated have in common. I welcome any feedback on my project from the ISCA community.

References

Chopik, W. J., Edelstein, R. S., van Anders Sari, M., Wardecker, B. M., Shipman, E. L., & Samples-Steele, C. R. (2014). Too close for comfort? Adult attachment and cuddling in romantic and parent–child relationships. Personality and Individual Differences, 2014/69, 212–216.

Debrot A, Stellar JE, MacDonald G, Keltner D, Impett EA. (2021). Is Touch in Romantic Relationships Universally Beneficial for Psychological Well-Being? The Role of Attachment Avoidance. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 2021/47(10), 1495–1509.

Maclarem, K. (2014). Touching Matters: Embodiments of Intimacy. Emotion, Space and Society 2014/13, 95–102.

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2008). Adult attachment and affect regulation. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (2nd ed., pp. 503–531). Guilford Press.

Gan, Y. M., (2020 [unpublished]) Choreographing Affective Relationships across Distances: Multigenerational Engagement in Video Calls between Migrant Parents and Their Left-behind Children in China (Doctoral Dissertation). The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China.

Goodwin, M.H., & A. Cekaite, (2018). Embodied Family Choreography: Practices of Control, Care, and Mundane Creativity. Oxford and New York: Routledge.

Goffman, E. (1959). Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York: Doubleday Anchor.

Goffman, E. (1971). Relations in Public: Microstudies of the Public Order. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Katila, J. (2018). Tactile intercorporeality in a group of mothers and their children: a micro study of practices for intimacy and participation.Academic Dissertation. Tampere University Press, Tampere.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1962). Phenomenology of Perception. London: Routledge.

A paper entitled as “Hugging and Kissing a Dog in Distress” (Lohi & Simonen 2021) offers perspectives on kissing in institutional interaction and suggests that “kissing can be considered a social action which functions as a “relationship marker” (Goffman 1971: 43) in both mother-infant and dog owner-dog interactions, signaling who is with whom.” Human adults’ interaction in lines 6 and 9 (Figures 5 and 7) may work similarly. Moreover, Berducci (2016) has analyzed sporadic and continuous kissing. See also Kendon (1981, 1990) and Wright (2011).

Hi Simo, thank you for these useful references! I’ll be sure to look into them.

Thanks for this fascinating analysis. I wonder if watering the flowers does not carry subconscious connotations related to the touching episode that might resonate or reverberate in the continued togetherness of the two people. I am interested in the use of talk as intimacy, so the moment at which talk becomes the performance of intimacy. In this case, the nursery rhyme could be seen as having that function. I would love to read more of your analysis of this material.

Dear Johan, thank you for your comment! the song indeed serves as a performance of intimacy here. interestingly, there are other cases of singing too, in my data. watering the flowers, too, can be seen as contributing to the things that matter for the participants and their relationship– caring for their home. (watering the flowers perhaps analogous to watering the relationship :-))